Implementing the Research

Your preparation work should have got you to a point where you are now quite comfortable with research ideas.

Having worked your way through Phase 1, your class should now be familiar with the CEPNET state of mind, where they are now ruling the roost and your role has become that of facilitator. This will become even more pronounced as we move through Phase 2.

Your students are more than likely used to project work, but as we know this time with CEPNET, it will be different. They will be taking their interests and shaping these into research questions, forming groups and becoming action researchers, analysts, writers, music composers, interviewers, podcasters, artists, designers, beach cleaners, activists, community workers and taking on a whole lot more roles yet to be defined…

So within this module, these are the important “how to” steps for your consideration

- considering a research question

- designing a research process

- putting this plan into practice

- framing a final product

Through your planning work, you will be now aware of the types of research activities that your students might decide to use as part of their project work. Keep these in the back of your mind as they now start into the first important challenge- refining the nature and focus of their project.

1. Refining the research question

The students will start into Phase 2 of the work with a good sense as to what their job is over the coming weeks. At this stage, they have discussed and debated the SDGs and they have discovered a topic that they are interested in. Ideally, they have formed groups around these interests. These groups may shift and alter in the first session of Phase 2, but you are looking to get the students settled and organised for their research work.

Just to remember that it was so important that the subject matter was being decided by the student.

Having being in charge of their topic, now their main challenge to begin the research work is to narrow down this topic of interest so that they can come up with a research question. You can approach this with them in a number of ways.

You can ask them to develop a hypothesis that they would like to understand more about or even prove. This might seem complicated, but if you break it down into simple ideas, they will get it. The idea is that they can put together their focus as “if” something has happened/ is happening, “then” we expect that this will be the result. So for example, some students looked to better understand the relationship between eating habits of their peers at lunchtime and the impact on sustainable practices within the school. Their hypothesis became that “if” we all know more about food miles, “then” we can change what we put in our lunchboxes to become more sustainable. This project became a very effective study as to what over 250 children were eating every day at lunchtime.

Another approach to the research can be a deep dive into a subject matter that is important to them. In this instance, it is still important that they can have a research question that can focus their minds and activities. But this approach makes it slightly easier to conceptualise their project work, but there is a danger that they can go off on many tangents and get sidetracked along the way. This of course is no harm and can force them to make decisions about where to go next and when to call a halt. This type of approach was very common with our students. They covered a wide range of issues such as homelessness and housing for young people, being an asylum seeker and how you are treated by society, women in sports and clean energy options in their area. Such themes motivated the students and allowed them the opportunity to carry out important studies.

Other students were motivated by action projects. In these instances, the students already knew at an early stage that they wanted “to get out and do something”. Your job is to facilitate them as much as possible, but also to make sure that their focus for the action is grounded in a study or research into the particular topic. Many groups were motivated by issues of pollution and environmental degradation that had been discussed in Phase 1. These dialogues had inspired them to carry out a clean up of a local facility, such as a playground or even their school. Others were focused on marine pollution and wanted to carry out beach clean ups. Others were interested in carrying out a fundraiser for an organisation working around their theme of interest. These types of projects are to be encouraged, but they will need some extra support along the way. For instance, the action will invariably take place outside of school time and transport will need to be arranged by the groups. In all cases, these aspects worked out fine, but just be aware that the students need to consider these elements, as they are refining their focus.

There are other types of projects that might arise, such as developing a campaign or producing an artistic response. Again, these are laudable options and the students are to be encouraged. There may be a desire to jump straight into the final version of the project, so these students need to be supported to break down their ideas at this initial step to consider exactly their focus.

For all the students, at this initial introduction into research and research questions, there will be an urge to get online and start looking up websites on their topic. This can be overwhelming. So from the teacher and facilitator point of view, as your students are now considering their “big interest” and trying to modify this into a specific research question, you can provide the support that follows here to help them come up with clear questions, getting them to be as realistic as possible as they narrow down the focus.

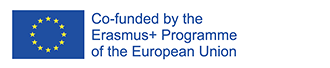

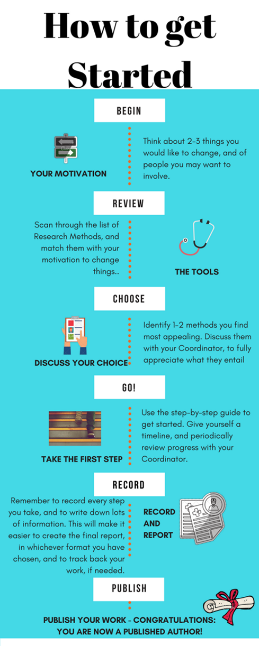

These checklists proved very useful with our teachers in helping to get their students into the “thinking space” for doing research. First up, they had to think about how to get started on their research idea and then how to do an online search. It is important to continue the discussion from earlier about what constitutes reliable news sources and the notion of “fake news”. The students may be drawn to the most dramatic or over the top stories, emerging from a social media feed. Often the story has come from the school yard or an older sibling and has been exaggerated along the way. The students can be encouraged to examine the source and its validity. They can examine further sources for the same story to see if it checks out. Let them develop a list of reliable news sources as they continue this initial research work.

Getting Started on their Research

Examining sources and searching online

The Google Search Education website provides lessons at different levels and includes slideshows and videos. It’s also home to the A Google A Day classroom challenges. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords. This site also can provide some guidance if the students want some extra support. Take a look here to learn more about “instant searches” and here for 12 simple search tips, which can be useful once students master the basics too.

During these sessions, you are aiming that each of the research groups are one by one, ticking off that they have now found out enough about their topic and area of interest to be able to move onto the next step, which is developing a project plan. If they are not there yet, you can get them to have a go at some mindmapping- another useful tool to help them to become more selective in their searching and more specific in their research focus. Here is a simple introduction to using mindmaps.

While this initial “searching, re-searching and focusing” work is ongoing, it’s also never any harm for you to keep up to date with external research reports and materials on the SDGs just to keep informed. For instance, this resource offers a range of activities that can be used in classroom settings. Have a look and see if they can fit with your class.

As the project groups are now beginning to coalesce around themes and topics of interest, you can now start pushing them to write down their research question or even the name of their group if they are still struggling to narrow down their topic. There is no problem with this taking some time. Some groups will be quicker to focus than others. It’s of course an idea to bring them back to the SDG that is the basis for their interest and let them review the Phase 1 videos and and resources if they still need some extra help at this stage.

Our teachers have some good ideas for you to consider.

As ever, you can check in on the lesson plans and the slides to get some inspiration and to see how our teachers have managed this step along the way.

2. Selecting the research methods

Once the groups have managed to work out their research question and be warned, this may change a number of times over the next few sessions as they continue to debate, argue and research the topic further…

This second step focuses on getting each group to put a project plan together. Again, this does not have to be written in stone, but it will give the more organised groups a clear roadmap for the coming weeks and sessions. Also for the less organised groups, it will force them to have to at the very least consider who will be responsible for what task and when will they be doing it…

The following template is crucial. Sit them all down with this and talk them through it.

The Research Toolkit that we referred to in the Preparation stage might be useful at this stage. It might be slightly advanced for primary school students, but you might get some ideas to help them come up with the types of research techniques that could be used. Talking about “data collection techniques” can sound scary to the children, but if you can explain it in terms of naming the ways in which they will go about doing their research, this might make it more straightforward.

These are the main issues to focus their attention as they are working on the template in their groups:

- Examining the research tasks within their group, making a list of these tasks, using the template

- Thinking about research tools- do these need to be designed?

- Skills audit – who is good at what? Keeping records

- Most importantly a group discussion on who is going to do what?

- Once agreed, making a list where responsibilities are allocated and a realistic timeline added

The groups can be assisted in their planning. It is probably done best by working with each group individually and making sure that they are now ready to work away by themselves, using this template as their guide.

3. Carrying out the research

Now that the groups have their project plan that is connected to addressing their research question that in turn is linked to their big interest (that in turn is linked back to one of the SDGs), they are free to work away. While most of the research work and tasks can be carried out in the classroom time slots that have been allocated to delivering CEPNET, there may also be the need for some research time at home. This can be hopefully followed up with parents or guardians.

During the CEPNET class periods, they may be spending time using laptops or tablets or other devices to carry out secondary research online or using Zoom to conduct interviews with experts or specialists in the chosen field. They may be designing a questionnaire. They may be using the time to survey other classes or teachers in your school.

If they have already collected information from their surveys, etc. they may be using the time to analyse the data.

In our experience, these sessions became quite “lively” in terms of the volume of discussion and work. The more organised groups were working ahead and sticking to their project plan. The less organised groups often became quite phased by the tasks ahead. Our teachers felt that it was important to keep involved with these groups, even from a distance, to make sure that they were not falling too far behind the CEPNET schedule.

In some instances, circumstances beyond their control caused a hold up. We experienced some delays in awaiting answers from local politicians and even from the Minister. While these snags were eventually sorted out (see here for the resolution of this particular political issue), it often meant that some groups struggled to fill the class based time as productively as they would have liked. It’s an idea to encourage such groups to be thinking about other elements in their project plan if this is the case.

As mentioned earlier, it is important that the parents and guardians are aware of the project work that is being carried out, as they may be called into action at this stage. In some projects, there were lifts required at weekends when the children were looking to go to the local beach to carry out a clean up. One of our principals emphasises the importance of the parental and guardian engagement.

It is useful once again at this stage to let your students have a look at the project archive and see how different projects were carried out in the different schools.

They can find examples of the following project types:

- The deep dive into a subject area

- An action project involving a clean up

- A survey and analysis project

- A multi-method project

By reviewing these examples, they can get fresh ideas and start to think about what the final version of their project will look like. These other projects can demonstrate the use of questionnaires or parents and students, interviews with experts, online petitions and use of survey monkey as well as writing letters and emails to NGOs and other specialists.

Our teachers found that it was important to remind the groups to always maintain their records and their research progress. For some groups, it suited to have their work saved online. For the group that developed a blog relating to the climate crisis with individual entries on topics of interest, their work was being updated as they progressed. For other groups, an artistic or creative output was being developed over time, so they needed space in the classroom to store their work. Each group might need some support in this area, especially at the start.

Where possible, any opportunities for organising online interchanges between groups of children and other schools locally, nationally of internationally works very well at this stage. It can spur some of the groups on so that they have some material to share with their peers.

4. Considering the final project

How the children choose to pull the information together will again be down to them, but no harm for you to have some ideas up your sleeve.

The following ideas are worth exploring with your groups:

- They may want to make a poster, produce a PowerPoint presentation or even a report on their new information.

- They may be more creative and use rap, rhyme or art.

- They may use more digital tools, such as a podcast, video or a sound recording.

As earlier, it is no harm to show them completed projects from the archive section of the website. Let them check out some of the videos of student presentations. Again, this will let them get an idea as to what they will be doing in Phase 3 when it comes to sharing their work.

As they are working their way to the end of Phase 2, their research is being concluded and they are planning what it will look like, the temptation might be to step in and help them to “professionalise” the final look of their project. However, as they are doing this work and looking to create the best means from their viewpoint to demonstrate the results of their research, we have to go back to our main lesson and that again is all about you as facilitator and as the adult to stay in the background, offering support when asked… It’s not so easy, but by this stage you are getting good at it.

They will be guided by their own project plan using their CEPNET research template. By following their plan, you will be assured that this allows the groups to forward plan to the presentation stage and can be completed throughout the 4 weeks of the research phase and furthermore helps them at this point in selecting the type of artefact they will chose to reflect their findings.